How Does Creativity Work in the Brain?

Let’s jump right in and explore creativity scientifically. Cognitive neuroscience demonstrates that “new” ideas are generated by combining old ideas.

Let’s jump right in and explore creativity scientifically. Cognitive neuroscience demonstrates that “new” ideas are generated by combining old ideas into new, unique elements. Easy enough so far, right? It means that the way creativity works in the brain must already use elements that exist in some way. So actually, it takes a lot of pressure off of creators—artists, authors, inventors, problem-solvers—really, everyone!—when they try to come up with “new” things. All new things are really unique combinations of old things.

Of course, I don’t mean to condone plagiarizing or simply copying other ideas, slapping a few new labels on them, and calling them good! The key is making unique combinations, and carefully selecting existing elements to shape into something that the world could find novel value in.

For example, most of us would consider J. R. R. Tolkien a very creative author. However, cognitive science reveals that Tolkien could not write The Lord of the Rings without combining prior influences in new ways—which Tolkien himself reveals in his own recommended construction for good works of fantasy (his essay “On Fairy-Stories”). He has many sources in medieval literature and openly lets himself be influenced by them. However, he adds new details to his complex combinations of these sources to build a very unique world for his stories.

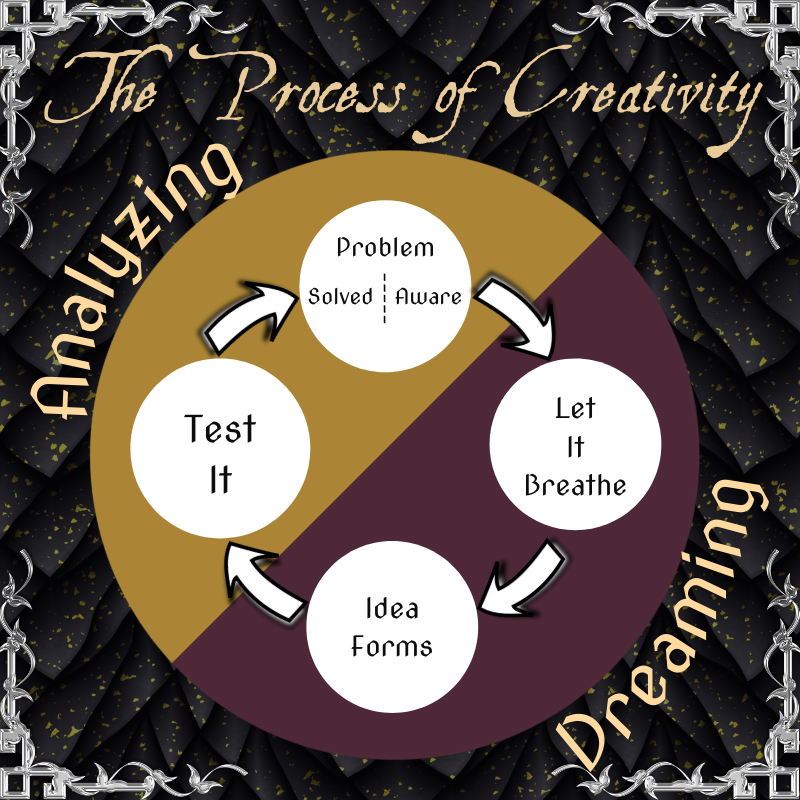

How does this kind of creativity happen in the brain? Famous cognitivist Colin Martindale explains this through the terms primary and secondary process thinking. Martindale states, “Primary process thought is found in normal states such as dreaming and reverie” (138). So think of those times you lose yourself in mostly subconscious thought. In these more unconscious states, “strange powers of the mind may be unlocked” (41). In other words, have you been so focused on a problem, maybe trying to remember a name or what you entered a certain room for, only to move on to something else and then suddenly have the solution occur to you? Yeah, this is what brain science is getting at.

However, these subconscious thoughts must be brought into consciousness for creativity to occur. “Secondary process cognition,” then, “is the abstract, logical, reality-oriented thought of waking consciousness,” in which the judgment and selection of ideas takes place (138). In other words, those thoughts have to be made available to you, so you can actually do something with them!

Let’s look at that process in a little more detail. According to Martindale’s analysis of Helmholtz and Wallas’s four stages of the creative process, “preparation, incubation, illumination or inspiration, and verification or elaboration,” one must move between these two cognition processes with their different levels of brain activation to achieve the final stage of creativity (137-138). Preparation simply means learning or thinking about things that might help to solve some problem. But solving a complex problem is usually not that easy. Those things you learned or thought about have to stew for a while. This is where you sleep on it, or do some other task for while—the incubation period. Then the part that seems like magic, when the solution finally just comes to you, is the illumination or inspiration stage. Great! Now you need to apply logic to your solution to hone it down into something great—verification or elaboration. (138).

The reason this works is because during the preparation stage when you’re trying to come up with some new book idea, the nodes in your brain working on it are working so hard that no other elements can come in. You’re actually too conscious of your problem—or the idea you’re trying to work out. But this is still a necessary stage. What’s really happening in your brain is that these activated nodes are storing away all those pieces you think might be related to the problem.

Then, when you finally lay off the problem—and your hard-working brain nodes—creativity can happen. Those nodes may no longer be fully lit up, but they are still glowing while you do other things. Martindale notes, “Of course, the creative solution lies in ideas thought to be irrelevant . . . . As the creator goes about his or her business, many nodes will be activated. If one of these happens to be related to the nodes coding the problem, the latter became fully activated and leap into attention. This is inspiration, the discovery of the creative analogy” (“Creativity” 256).

This is the really awesome part. You’ve become conscious of all that work your subconscious was doing behind the scenes. You have a working solution—or idea, or whatever it is. But now it’s time to verify it. This is where the editor side comes in. Is the solution practical? Could something make it not work? Once again, you focus conscious attention on your solution and original problem to search for any “flaws” (“Creativity” 256).

How is knowing all this brain science on creativity useful? Martindale asserts in “Creativity and Connectionism” that “[c]reative ideas often involve taking ideas from one discipline and applying them to another” (252). This process follows with Martindale’s definition of a creative idea as “one that is both original and appropriate for the situation in which it occurs . . . always consist[ing] of novel combinations of preexisting mental elements” (“Biological Bases” 137). Therefore, Martindale believes “[i]t would seem that to maximize creativity, one’s best bet is to have knowledge about a wide variety of things,” and cites studies demonstrating that “creative people have a very wide range of interests” (“Creativity” 252). This broad knowledge, Martindale proposes, makes it easier to have a moment of inspiration (the third stage of the creative process under primary process thinking) (256).

If you’re like me and actually have a hard time juggling all your hobbies and eclectic interests, at least you can rest assured (and productively!) in knowing that you have a good foundation for creative ideas to occur. And all those times spent procrastinating rather than really working? They’re just creative incubation time! Get away from the problems—after you’ve thought nice and thoroughly about them for a while first—and see what happens! So, to be “more creative,” try learning about something related to your problem. Learn about something different! Then work on something else—or better yet, sleep! Engage in other interests. Once your crazy powerful brain makes some amazing, magical connections, then you can go back into judge mode and use all the logic you want. You can forget that magic ever even happened and ruthlessly hack your solution apart and build it back up, reshape it, elaborate on it, to make it into something great.

Happy creating!

Sources referenced include the following books and sections on creativity and cognitive science:

Martindale, Colin. “Biological Bases of Creativity.” Handbook of Creativity. Ed. Robert J. Sternberg. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1999. 137-152. Print.

---. “Creativity and Connectionism.” The Creative Cognition Approach. Ed. Steven M. Smith, Thomas Ward, and Ronald A. Finke. Cambridge: MIT P, 1995. 249-68. Print.

I also highly recommend

Hogan, Patrick Colm. Cognitive Science, Literature, and the Arts: A Guide for Humanists. London: Routledge, 2003. Print.

Others to consider:

Brophy, Kevin. Patterns of Creativity: Investigations into the Sources and Methods of Creativity. Amsterdam: Rodopi, 2009. Print.

Segal, Erwin M. “A Cognitive-Phenomenological Theory of Fictional Narrative.” Deixis in Narrative: A Cognitive Science Perspective. Ed. Judith F. Duchan, Gail A. Bruder, and Lynne E. Hewitt. New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum, 1995. 61-78. Print.

Turner, Mark. “Double-Scope Stories.” Narrative Theory and the Cognitive Sciences. Ed. David Herman. Stanford: CSLI, 2003. Print.

Categories: : creativity

THE DIY ROUTE

If you would like more resources and writing craft support, sign up for my FREE 3-Day Validate Your Novel Premise Challenge email course. You will learn how to check if you have a viable story idea to sustain a novel and then follow the guided action steps to craft your premise for a more focused drafting or revision experience in just three days.

THE COURSE + COACHING ROUTE

Cut through the overwhelm and get your sci-fi/fantasy story to publishable one easy progress win at a time! I'll coach you through the planning, drafting, and self-editing stages to level up your manuscript. Take advantage of the critique partner program and small author community as you finally get your story ready to enchant your readers.

EDITING/BOOK COACHING ROUTE

Using brain science hacks, hoarded craft knowledge, and solution-based direction, this book dragon helps science-fiction and fantasy authors get their stories — whether on the page or still in their heads — ready to enchant their readers. To see service options and testimonials to help you decide if I might be the right editor or book coach for you,

Hello! I'm Gina Kammer, The Inky Bookwyrm — an author, editor, and book coach. I give science fiction and fantasy authors direction in exploring their creativity and use brain science hacks to show them how to get their stories on the page or ready for readers.

I'll be the book dragon at your back.

Let me give your creativity wings.

This bookwyrm will find the gems in your precious treasure trove of words and help you polish them until their gleam must be put on display. Whether that display takes the form of an indie pub or with the intent of finding a traditional home — or something else entirely! — feed me your words, and I can help you make that dream become more than a fantasy.

Gina Kammer

Gina Kammer